On February 25 (Beijing time), Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute (TCCI) and the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) co-hosted the Contemplative Science Summit. The conference consisted of three symposiums that jointly explored how does contemplative science get out of the lab and become an integral part of the world in order to better study the impact of contemplative practices that will be incorporated into society in a more meaningful and impactful way.

COVID-19 has profoundly changed the living style of everyone and has contributed to the development of the contemplative science, propelling relevant research to get out of the lab and into the world. Contemplation has gradually become better known as an effective self-help method, but the neural mechanisms behind it are still unclear. Symposium 1 focused on embedded measurement systems and remote technologies, how can effective research be conducted in exploring the true impact of contemplation on people’s lives? How can remote data collection technologies help?

At the early days of the pandemic, everyone was living in uncertainties, with a lost sense of security while suffering from huge pressure and anxiety. Dr. Quinn Conklin, Dr. Brandon King and Dr. Alea Skwara from UC Davis have shared their contemplative studies during the pandemic from different perspectives.

01 Contemplative research in context: Insights from COVID-era research and intensive retreat studies

Quinn Conklin, Ph.D., Brandon King, Ph.D., & Alea Skwara, Ph.D., University of California, Davis

Contemplative solutions to cope with COVID-19

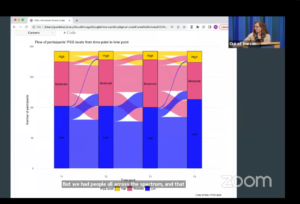

Contemplative practices can help people relieve stress and anxiety, but there are individual differences in its effectiveness. To investigate whether contemplation helps people cope with uncertainty and the stress it causes during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers recruited hundreds of volunteers from different countries and collected information from multiple perspectives to reflect the volunteers’ resilience, mental toughness, and physical condition through questionnaires and a remote blood-collection toolkit. In order to make the results of the study available to a wider audience, they visualized the data and uploaded it to a website they created. The website allows users to visualize the data from different dimensions to see how the data relates to each other.

Taking stress perception as an example, users are able to observe individual differences in stress perception by adding variables such as age, region, and contemplation, respectively. In addition to this, the website can also monitor the relations amongst the variables through the correlation matrix. The site is constantly being iterated and optimized, while continuously accumulating data and breaking down the data into more detailed dimension. Users will have more freedom to explore the content of their own interests.

How does contemplation affect people’s perception of pain

When we contemplate, we may enter a state of oblivion. Our minds are unrestrained, and our imaginations run wild. One moment we are thinking about the role of nature, and the next we may start pondering over the social environment and changes in our daily lives. What kind of changes will contemplation bring us? Researchers have found that contemplation increases the motivation to feel pain through a three-month intensive retreat contemplation study.

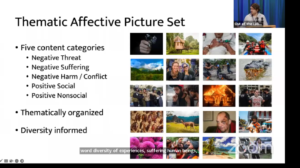

They divided 60 subjects into a retreat group who spent three months at a retreat center on contemplation and a control group who went about their normal lives at home. The researchers created thematic affective picture sets that contained emotional stimuli on a variety of topics such as threat, suffering, and harm, including negative topics such as interpersonal conflict, natural disasters, unemployment, homelessness, and conflict and harm between different groups, as well as positive topics such as positive human-human interactions and positive human-animal interactions. When given emotional stimuli, the retreat group’s perception of pain was more prominent, probably because of the different level of importance for the retreat group and the control group when it comes to pain.

They presented this picture set to 250 college students and asked them to rate the pictures based on two dimensions: positive vs. negative and approach vs. escape. They found that for painful stimuli, while most gave negative ratings, unlike threats, not everyone wanted to flee, possibly due to individual differences in terms of empathy. Those with higher empathy perceived the painful pictures as more negative but had to approach the pain in order to resolve it and to understand its origin. However, are there other explanations for this propensity? Can this propensity be acquired through training? What is the nature of this shift? What does it mean to feel disgusted and desired to approach at the same time? How is it developed? What is the physiological nature of this phenomenon?

Exploring remote and online contemplative interventions

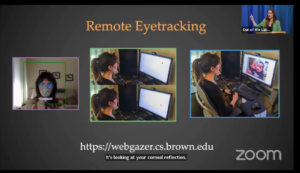

To address these issues, they planned to conduct an eight-week contemplation training in the laboratory to explore the relation between visual attention and physiological responses and their short-term changes evoked by painful stimuli. However, as the epidemic interrupted the experimental process, they explored ways to study online contemplative interventions remotely.

To ensure the quality of the data collected, they worked with participants to construct home labs. High-quality cameras and online eye movement analyzers helped researchers collect eye movement data and model pupil movement to reflect their visual attention. Specialized smartwatches were able to measure the subjects’ heart rate and skin conductance to reflect their physiological conditions. The study collected subjective reports from 275 instructors who taught online as well as in face-to-face classes. The data showed that the intervention was slightly less effective for online practices; however, reports from students who received contemplation training showed that staying at home instead strengthened their contemplative practices attributable to a sense of online community.

This online means of collecting data on contemplative interventions has reduced accuracy and variability, but it is ecologically valid. It is more inclusive of diverse participants, which makes it plausible to explore a wider range of issues. They are now initiating a pilot study in a larger group.

02 Capturing the natural unfolding of memory for events encountered under threat and curiosity

Vishnu Murty, Ph.D., Temple University

Memory is not an authentic record of past experiences but affected by internal states. Dr. Vishnu Murty of Temple University discusses how do the two states of threat and curiosity affect memory.

Selectivity of memory

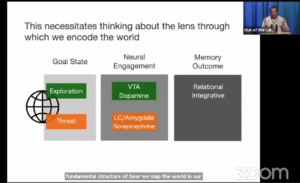

In our memories, some information is lost while some is always there. Everything we see in the world is filtered through goals and desires, and we receive exactly the same stimuli, but our preferences for those stimuli will change the landscape of our memories. Memory is driven by a person’s internal state and the selectivity of memory is usually focused on emotionally relevant aspects.

Exploration state and threat state

When in an exploratory state, the nucleus accumbens (NAC) is activated and dopamine secretion increases. When in a state of threat, there is increased secretion of the stress hormone (cortisol), activation of the amygdala, and increased secretion of norepinephrine. When in an exploratory state, we represent more of our relationships with the surrounding world, and when in a state of threat, we get more project-centered representations. So how do goal states affect memory in the brain? Why does threat lead to memory fragmentation?

Threat and exploration models

Through experiments in navigating virtual reality environments, researchers have found that people would memorize signposts during exploration in order to build a map that helps identify hidden locations. However, threatening information near a signpost would destroy people’s memory of that signpost. In this state, threatening information actually destroys memories increased by exploratory curiosity.

If we really want to understand what’s going on, we need to introduce a motivational filter. The hippocampus is responsible for exploration and likes to make relational memories, binding content to context to make a comprehensive map of the world around it. The peripheral cortex of hippocampus, on the other hand, is responsible for danger recognition and is good at remembering specific things but can’t incorporate them into a relational map. Thus, even though everyone receives exactly the same information, their mental state at the moment changes how that information is stored.

Haunted house experiment

Researchers constructed the haunted house laboratory inspired by actual startles. Subjects would wear a device that could measure their heart rate before entering the haunted house to undergo a pre-arranged startle test and later report on the startles they received. The researchers found that the more a person’s heart rate rose, the more biased their perception of specific parts of the haunted house became, which also interfered with the way people narrated threatening events. As we move through space, the sense of threat can dynamically shape what we extract from the world.

They also found that threat exerts no influence over the ability to remember things but interferes with curiosity to prevent us from noticing the things worth our attention.

Inspired by mindfulness and contemplation, their team explored whether curiosity could be used to mitigate the negative effects of threat. At the beginning of the study, they asked subjects to say nine statements that they feared their peers would say, and in this way, they obtained self-related threats. The classic method of emotional regulation is to reduce or increase emotions through reassessment. Using this technique (curiosity about why they said what they said), negative emotions about the words could be similarly reduced.

In addition, using curiosity is much easier than cognitive reassessment. There appears to be a push-pull relationship between curiosity and threat and their effects on memory. While threats may inhibit our intrinsic curiosity for a moment, we can use curiosity techniques to inhibit the effects of threats.

03 App-based contemplative trainings: Promises and pitfalls of scalability.

Paul Condon, Ph.D., Southern Oregon University

Mindfulness contemplation and compassion contemplation can diminish the bystander effect and increase helpful behaviors. App-based contemplation training can also achieve this effect. This training method is also effective in reducing stress and improving sleep. But it’s not without its drawbacks. Dr. Paul Condon of Southern Oregon University found that people were more likely to give up when participating in app-based contemplative trainings than in face-to-face contemplative trainings, and that mindfulness practices reduced some people’s willingness to help, which means that contemplation made them more selfish. Why’s the possible explanation to this?

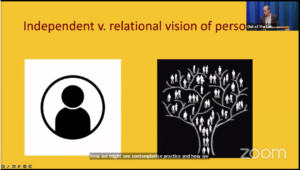

Face-to-face training can help people construct social connections with mentors, peers, and even caregivers, embedding people in social relationships and deepening interpersonal bonds. When people are not in such social relationships, they do not feel socially supported during contemplation and are more likely to experience burnout, aversion to pain, and loneliness in their suffering.

The point of a contemplative practice is to help people experience the cycle and strengthen it. People can build an inner sense of security and then extend that feeling to others by viewing and supporting them in the same way, and others can in return enhance this sense of security. Dr. Condon and his collaborators proposed this concept and used it as a relational starting point for contemplation.

Contemplation can bring calm and serenity to the mind, but researchers have yet to fully figure out why it works. This first symposium of the Summit takes us through the scientific explanations behind this ancient and mysterious way of life, and the app-based practice of contemplation is a key step in taking it out of the lab and into the world. We hope that contemplation will have a positive impact on more people’s lives.