NeuroAI: Can It Lead Neuroscience Out of Its Impasse?

On a city street, a self-driving car is moving. Suddenly, a child chasing a ball dashes into the road. The car’s multiple onboard sensors immediately capture the situation—cameras, LiDAR, and millimeter-wave radar all operate simultaneously, while dedicated neural network processors and GPUs begin high-speed computations. Under peak conditions, the entire system consumes hundreds of watts of power and, through parallel processing, completes the perception-to-decision process in approximately 100 milliseconds.

In the same scenario, however, a human driver can hit the brakes in an instant. In such complex situations, the human brain consumes only about 20 watts of power—comparable to a small light bulb. Even more astonishingly, the brain, through distributed parallel processing, simultaneously manages countless tasks, such as breathing and regulating heartbeats. It performs parallel computations with extremely low energy consumption, learns quickly from limited experience, and adaptively handles a wide range of unforeseen situations.

This enormous efficiency gap has spurred scientists to pioneer a brand-new field—NeuroAI (neuro-inspired artificial intelligence). This emerging discipline seeks to overcome the limitations of traditional AI by mimicking the brain’s operational methods to create smarter and more efficient systems. For example, researchers draw inspiration from how the brain processes visual information to improve computer vision, reference neuronal connectivity patterns to optimize deep learning networks, and study the brain’s attention mechanisms to reduce the energy consumption of AI systems.

This article will take you on an in-depth journey into NeuroAI, reviewing its definition, development history, current research status, and future trends. It will also examine how NeuroAI simulates the brain’s learning mechanisms, information processing methods, and energy utilization efficiency—and how it addresses the bottlenecks currently faced by AI—in light of the latest research presented at a recent NeuroAI symposium hosted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

What is NeuroAI?

NeuroAI exemplifies the two-way integration of artificial intelligence and neuroscience. On one hand, it leverages artificial neural networks as innovative tools to study the brain, thereby testing our understanding of neural systems through constructing verifiable computational models. On the other hand, it draws on the brain’s operational principles to enhance AI systems, transforming the advantages of biological intelligence into technological innovations.

For years, the fundamental goal of AI research has been to create artificial systems capable of performing every task at which humans excel. To achieve this, researchers have consistently turned to neuroscience for inspiration. Neuroscience has spurred advancements in artificial intelligence, while AI has provided robust testing platforms for neuroscience models—forming a positive feedback loop that accelerates progress in both fields.

The relationship between AI and neuroscience is genuinely symbiotic rather than parasitic. The benefits that AI brings to neuroscience are as significant as the contributions of neuroscience to AI. For example, artificial neural networks lie at the core of many state-of-the-art models of the visual cortex in neuroscience. The success of these models in solving complex perceptual tasks has led to new hypotheses about how the brain might perform similar computations. Similarly, deep reinforcement learning—a brain-inspired algorithm that combines deep neural networks with trial-and-error learning—serves as a compelling example of how AI and neuroscience mutually enhance one another. It has not only driven groundbreaking achievements in AI (including AlphaGo’s superhuman performance in the game of Go) but also deepened our understanding of the brain’s reward system.

The Development History of NeuroAI

The interplay between computer science and neuroscience can be traced back to the very inception of modern computers. In 1945, John von Neumann, the father of modern computing, dedicated an entire chapter in his landmark EDVAC architecture paper to discussing the similarities between the system and the brain. Notably, the paper’s sole citation was a brain study by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts (1943), which is widely regarded as the first work on neural networks and laid the foundation for decades of mutual inspiration between neuroscience and computer science.

▷ Figure 1. A depiction of the logical computing units in computers from von Neumann’s paper, inspired by excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Source: von Neumann, J. (1993). First draft of a report on the EDVAC. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 15(4), 27-75.

The concept of neural networks achieved a major breakthrough in 1958 when Frank Rosenblatt published a paper entitled “The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain.” In this paper, he first proposed the revolutionary idea that neural networks should learn from data rather than being statically programmed. This breakthrough was featured in The New York Times under the headline “Electronic ‘Brain’ Learns by Itself,” sparking an early surge of interest in artificial intelligence research. Although Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert pointed out the limitations of single-layer perceptrons in 1969—triggering the first “neural network winter”—the core concept that synapses are the plastic elements, or free parameters, in neural networks has persisted to this day.

In recent developments in artificial intelligence, numerous innovations have been inspired by neuroscience. One of the most prominent applications of NeuroAI is the highly successful convolutional neural network in the field of image recognition, whose inspiration can be traced back to the modeling studies of the visual cortex conducted by David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel forty years ago. Another example is the dropout technique, in which individual neurons in an artificial network are randomly deactivated during training to prevent overfitting. By simulating the random misfiring of neurons in the brain, dropout helps artificial neural networks achieve greater robustness and generalization capabilities.

Three Insights from the Brain for NeuroAI

Over the past decade, AI has made significant strides in various fields—it can write articles, pass law exams, prove mathematical theorems, perform complex programming, and execute speech recognition. However, in areas such as real-world navigation, long-term planning, and inferential perception, AI’s performance remains, at best, mediocre.

As Richard Feynman once said, “Nature’s imagination far surpasses that of humans.” The brain—currently the only system that flawlessly performs these complex tasks—has been refined over 500 million years of evolution. This evolutionary process enables animals to accomplish intricate tasks, such as hunting, with ease—tasks that contemporary AI still struggles to master.

This is precisely the direction that NeuroAI seeks to emulate: overcoming current AI bottlenecks by studying the brain’s operational mechanisms. In practice, this inspiration is reflected in the following aspects:

(1) Genomic Bottleneck

Unlike AI, which requires massive amounts of data to train from scratch, biological intelligence inherits evolutionary solutions through a “genomic bottleneck.” This process allows animals to perform complex tasks instinctively. In this process, the genome plays a crucial role: it provides the fundamental blueprint for constructing the nervous system, specifying the connectivity patterns and strengths between neurons, and laying the foundation for lifelong learning.

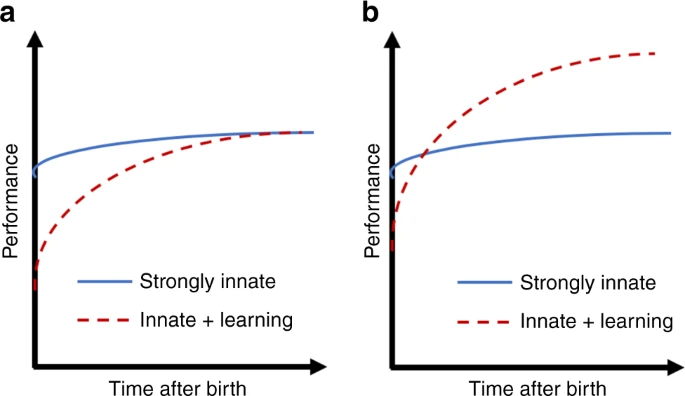

▷ Figure 3. Species that employ both innate and learned strategies tend to have an evolutionary advantage over those relying solely on innate instincts. Source: Zador, A. M. (2019). A critique of pure learning and what artificial neural networks can learn from animal brains. Nature Communications, 10, Article 3770.

It is noteworthy that the genome does not directly encode specific behaviors or representations, nor does it explicitly encode optimization principles. Instead, it primarily encodes connectivity rules and patterns that, through subsequent learning, give rise to concrete behaviors and representations.

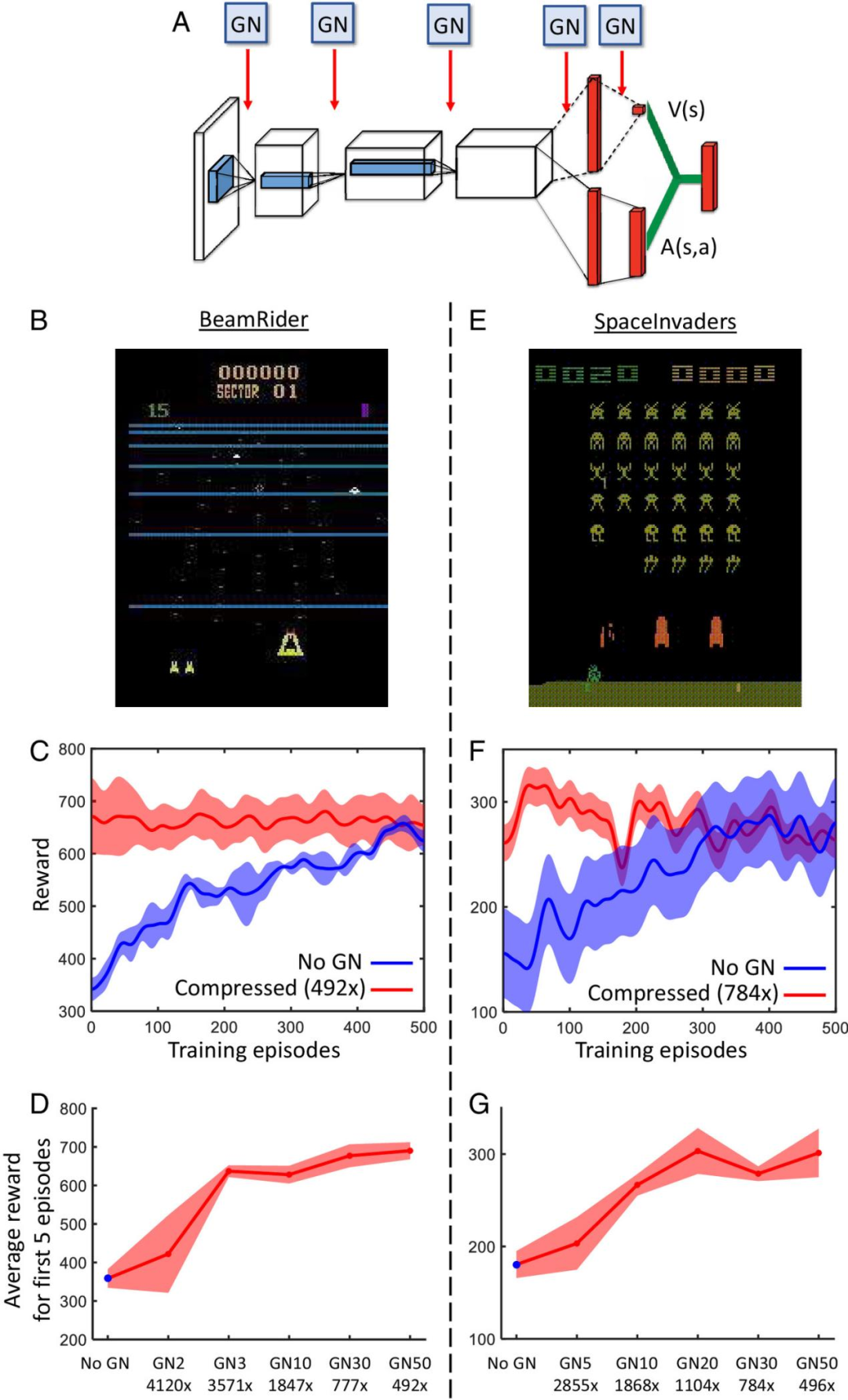

Evolution acts upon these connectivity rules, suggesting that when designing AI systems, greater emphasis should be placed on the network’s connectivity topology and overall architecture. For example, by mimicking the connectivity patterns found in biological systems—such as those in the visual and auditory cortices—we can design cross-modal AI systems. Furthermore, by compressing weight matrices through a “genomic bottleneck,” we can extract the most critical connection features as an “information bottleneck,” enabling more efficient learning and reducing dependence on large training datasets.

▷ Figure 4. Architecture and performance of an artificial neural network designed based on the genomic bottleneck principle for reinforcement learning tasks. Source: Shuvaev, S., Lachi, D., Koulakov, A., & Zador, A. (2024). Encoding innate ability through a genomic bottleneck. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(38), Article e2409160121.

(2) The Brain’s Energy-Efficient Approach

There is a vast discrepancy in energy consumption between artificial neural networks and the biological brain. Currently, models like ChatGPT require at least 100 times more energy for real-time conversation than the human brain consumes. Moreover, comparing the energy consumption of GPU arrays to that of the entire brain significantly underestimates the brain’s energy advantage—maintaining a conversation actually uses only a small fraction of the brain’s energy budget.

The brain’s remarkable energy efficiency can be attributed to two key factors: sparse neural firing and high noise tolerance.

First, most of a neuron’s energy is expended on generating action potentials, with energy consumption roughly proportional to the frequency of neural spikes. In the cerebral cortex, neurons operate sparsely, firing only about 0.1 spikes per second on average. In contrast, current artificial networks exhibit high spike rates and operate under conditions of elevated energy consumption. Although the energy efficiency of artificial networks has improved somewhat, we remain far from mastering the brain’s energy-saving computational mode based on sparse spiking.

Second, the brain is highly tolerant of noise. During synaptic transmission, even if up to 90% of spikes fail to trigger neurotransmitter release, the brain continues to function normally. This stands in stark contrast to modern computers, where digital computations rely on the precise representation of zeros and ones—where even a single bit error can lead to catastrophic failure, necessitating significant energy expenditure to ensure signal accuracy. Developing brain-inspired algorithms that can operate effectively in noisy environments could lead to substantial energy savings.

(3) Biological Systems Balancing Multiple Objectives

There is a marked difference between biological systems and current AI in terms of goal management. Modern AI systems typically pursue a single objective, whereas organisms must balance multiple objectives simultaneously over both short-term and long-term scales—such as reproduction, survival, predation, and mating (the so-called “4Fs”). Our understanding of how animals balance these diverse goals remains limited, largely because we have yet to fully decipher the brain’s computational mechanisms. As we strive to develop AI systems capable of managing multiple objectives, insights from neuroscience can provide essential guidance. Conversely, AI models can serve as platforms to test and validate theories of multi-objective management in the brain. This symbiotic interaction between neuroscience and AI research is propelling advancements in both fields.

Frontier Advances in NeuroAI Research

The intersection of neuroscience and artificial intelligence continues to deepen, with researchers drawing inspiration from biological intelligence systems and exploring scales ranging from microscopic molecules to macroscopic structures. Below is an overview of a series of innovative NeuroAI breakthroughs presented at a special symposium hosted by the NIH in November 2024, which enhance our understanding of the nature of intelligence.

1.Astrocytic Biocomputation

Living neural networks exhibit rapid adaptability to their environments and can learn from limited data. In this context, astrocytes—serving as carriers of information—play a critical role in the gradual integration of information within neural networks. This discovery offers a fresh perspective on the unique capabilities of biological neural networks and holds significant implications for both neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

2.The Feedback Loop Between In Vivo and Virtual Neuroscience

Recent advances in neurotechnology have enabled researchers to record neural activity under natural conditions with unprecedented coverage and biophysical precision. By developing digital twins and foundational models, researchers can conduct virtual experiments and generate hypotheses to simulate neural activity, thereby exploring brain function in ways that transcend the limitations of traditional experimental methods. This shift toward virtual neuroscience is crucial for accelerating progress and provides valuable insights for developing flexible, secure, and human-centric AI systems.

3.Advanced NeuroAI Systems with Dendrites

Dendrites, which serve as the receptive components of neurons, play a pivotal role in biological intelligence. Incorporating dendritic features into AI systems can improve energy efficiency, enhance noise robustness, and mitigate issues such as catastrophic forgetting. However, the core functional characteristics of dendrites and their applications within AI remain unclear, limiting the development of brain-inspired AI systems. Addressing this challenge will require interdisciplinary research to explore the anatomical and biophysical properties of dendrites across different species. With the aid of computational models and new mathematical tools, researchers can better understand dendritic functions, advance dendrite-based AI systems, and deepen our understanding of the design principles and evolutionary significance of biological systems.

4.The Future of NeuroAI: Drawing Inspiration from Insects and Mathematics

Although current AI systems are powerful, they rely on massive networks, enormous datasets, and tremendous energy consumption. Compared to natural intelligence, they lack key biological mechanisms such as neuromodulation, neural inhibition, physiological rhythms, and dendritic computation. Incorporating these mechanisms into AI to enhance performance remains an important challenge. Recent connectomics research on fruit flies has opened a new direction by drawing inspiration from the simple yet efficient biological brain. However, this approach faces significant mathematical challenges, particularly in managing high-dimensional, nonlinear dynamic systems like neural networks.

5.Learning from Neural Manifolds: From Biological Efficiency to Engineered Intelligence

Recent breakthroughs in experimental neuroscience and machine learning have revealed striking similarities in how biological systems and AI process information across multiple scales. This convergence presents an opportunity for a deeper integration of neuroscience and AI over the next decade. Research suggests that the geometric principles underlying neural network representation and computation could fundamentally change the way we design AI systems while deepening our understanding of biological intelligence. To realize this potential, several key areas must be addressed: 1) Developing new technologies to capture the dynamic evolution of neural manifolds across various time scales during behavior; 2) Constructing theoretical frameworks that connect single-neuron activity with collective computations to reveal principles of efficient information processing; 3) Elucidating cross-modal representational theories that explain the robustness of neural manifolds and their transformations, along with their underlying mechanisms; 4) Leveraging the efficiency of biological neural systems to develop computational tools for analyzing large-scale neural data. Interdisciplinary research spanning statistical physics, machine learning, and geometry promises to develop AI systems that more closely emulate the traits of biological intelligence, offering superior efficiency, robustness, and adaptability.

6.Advancing Toward Insect-Level Intelligent Robotics

Thanks to modern advances in control theory and AI, contemporary robots are now capable of performing nearly all tasks that humans can—from climbing ladders to folding clothes. Looking ahead, key challenges remain, such as designing systems that can make autonomous decisions and execute diverse tasks using only onboard computing without relying on cloud services. The fruit fly provides an ideal research model. With the complete connectome of the fruit fly’s brain and ventral nerve cord already mapped, we know that these tiny organisms can autonomously switch between multiple behaviors based on both internal and external states. However, to apply this model to robotics, higher-resolution connectomics data must be obtained and expanded to include more specimens. In addition, the connectomes of insects with more complex behaviors, such as praying mantises, need to be studied to better understand the relationship between neural architecture and intelligence. Finally, in-depth research into dendritic and axonal structures—beyond simple point-to-point connectivity—must be undertaken, along with the development of neuromorphic hardware capable of simulating millions of neurons that is readily accessible.

7.Mixed-Signal Neuromorphic Systems for Next-Generation Brain–Machine Interfaces

While traditional AI algorithms and techniques are effective for analyzing large-scale digital datasets, they face limitations when applied to closed-loop systems for real-time processing of sensory data—especially in the context of bidirectional interfaces between the human brain and brain-inspired AI, as well as neurotechnologies that require real-time interaction with the nervous system. These challenges are primarily related to system requirements and energy consumption. On the system side, low-latency local processing is necessary to ensure data privacy and security; in terms of energy, wearable and implantable devices must operate continuously with power consumption strictly controlled at sub-milliwatt levels. To address these challenges, research is increasingly turning toward bottom-up physical approaches, such as neuromorphic circuits and mixed-signal processing systems. These neuromorphic systems, employing passive subthreshold analog circuits and data-driven encoding methods, can execute complex biomedical signal classification tasks—such as epilepsy detection—at micro-watt power levels.

Afterword

As the field of NeuroAI continues to evolve, we find ourselves at a unique juncture in history: the deep integration of neuroscience and artificial intelligence not only helps us gain a deeper understanding of human intelligence but also inspires entirely new approaches to designing next-generation AI systems. From genomic bottlenecks to dendritic computation, and from energy efficiency to multi-objective balancing, the diverse characteristics observed in biological intelligence systems are reshaping our understanding of what intelligence truly is. Looking ahead, as brain science research deepens and AI technology advances, NeuroAI may spark a revolution in computational paradigms—enabling us to build artificial systems that more closely resemble biological intelligence. This journey is not merely about technological innovation; it is also a profound exploration of the nature of intelligence. In the process, we are not only creating new technologies but also rediscovering ourselves.

Reference: